How humans have got this far without all collectively dropping dead is a miracle.

By Nicole Buckler

Every now and again, we look through our back issues. We have all the issues dating back to 1914, and the National Library of Ireland holds the copies pre-dating these. Some of the stuff is fascinating, and some of it just is there to remind us how far we have come. So, so, soooo far.

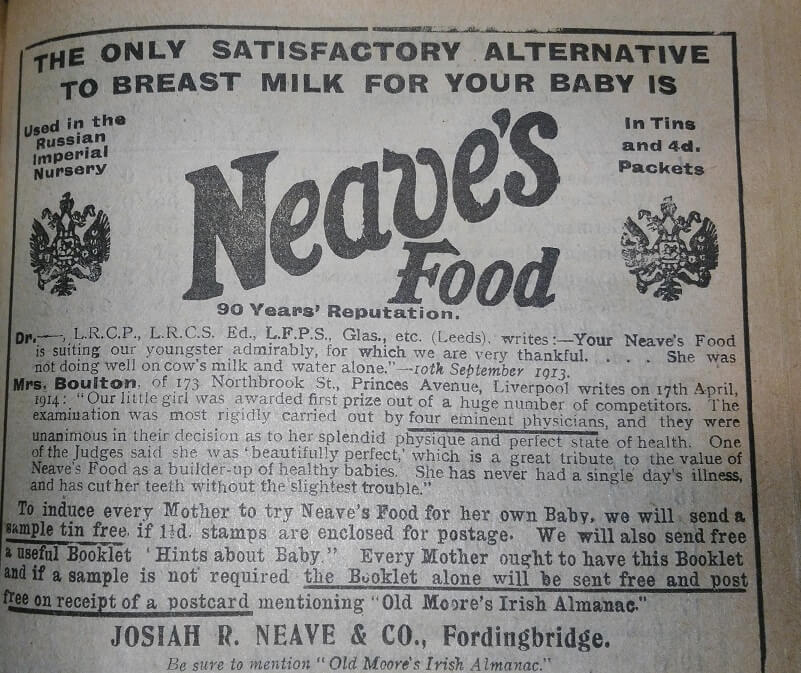

In 1916, the world was embroiled in a desperate war. So of course, advertisers of quack products went in for the kill. They had a field day peddling their pseudo-cures to a gullible public. And due to the popularity of Old Moore’s Almanac, the publication attracted these quack ads like flies to manure. A good example of this is a product called Neave’s Food.

Here we see Neave’s Food being peddled as a complete food for babies. Ads for Neave’s Food and other “infant Foods” were everywhere in 1916. These foods were a type of baby formula available before baby formulas became safe. If you Google the product enough, you’ll find many 100-year-old newspapers reporting on newborn babies dying after being fed a diet of such “infant foods” exclusively from birth. These “baby foods” were peddled excitedly in pharmacies of the day to ignorant mothers, who were told by advertisers that their products were endorsed by all sorts of medical people, most of whom were made up. Ah, the days before proper regulation, none of us feel nostalgic about that.

Products like Neave’s Food might have been vaguely acceptable as a weaning food, but as the only food for a newborn, it was a recipe for illness and death. The claims of such companies about their products were outrageous and dangerous. Testimonials from mothers who had supposedly used the gunk to make their babies into miraculous healthy wonders were wildly false and horribly misleading. One advertisement of such “infant food” of 1916 said:

“Doris until three months old had nothing but the breast: she then weighed only eight pounds and seemed to be wasting away from malnutrition. Then we tried Neave’s Food, and she immediately commenced to pick up, until today from a puny mite she has grown to be a fine strong girl with vitality and stamina that is simply wonderful.”

A writer of the time, Laurie Lee, recounted how his mother spent hours writing fictional testimonials to manufacturers (of things she never used) in the hope of earning a few shillings. They often used the letters without paying. Baby food advertising appeared in the medical journals, as well as newspapers, magazines, cookery books and even children’s books. Neave’s Food was recommended from birth with the endorsement, apparently, of the Russian Imperial Nursery. As it turned out, Neave’s Food could not save the members of the Russian Imperial Nursery from more powerful forces.

So what was in Neave’s Food? It’s hard to work out. But it seems it was a type of gruel – consisting of some type of cereal—oat, wheat, corn or rye flour, or rice—boiled in water or milk. It was a thinner version of porridge. It was grim stuff. Side effects of these inappropriate infant foods included diarrhoea, indigestion, constipation, flatulence, atrophy, or mouth ulcers. Awful.

One newspaper of the era reported a baby’s death after switching from breast milk to Neave’s Food:

The coroner (Mr. E. Whitfield) held an enquiry yesterday into the circumstances of the death of an infant, Dorothy Letitia Camm, while in the charge of Susan Matthews, at 141 Wellington-street. The first witness was Edith Camm, a domestic servant, the mother of the child, and a single woman living at Bridgenorth. The infant, she said, was six weeks old when it died. It was born at the Salvation Army Home, and when five weeks old was placed, with her consent, in the charge Mrs. Matthews, of 141 Wellington-street, who was to receive 4s a week. It had been a week with Mrs. Matthews when, at 5 o’clock on Monday, she heard of its death. The child was suckled while she had it, and when she handed it over to Mrs. Matthews, she bought Neave’s food for it. Susan Matthews, a married woman, corroborated the mother’s statement of the arrangement made when she took charge of the infant.

Susan Matthews fed it on the Neave’s food, and milk, and it took the bottle splendidly. On Saturday morning the child did not seem well. It was sleeping all day. Expecting the mother to call, in pursuance of an understanding, she waited for some time, but eventually about 5.30 went to the Salvation Army Home to ascertain what doctor the mother had had. On her return the child was dead, and Susan Matthews’ mother was laying it out. In answer to questions by Dr. Smith, she said she fed the child on Neave’s food, mixed with half water, half milk, boiled for 20 minutes. It took two or three tablespoonfuls every two or three hours. On Saturday afternoon her daughter informed her that the child seemed very bad. They gave it a little weak brandy and water. It got worse, and having sent her daughter to find where its mother was, she looked after the infant, but in about twenty minutes it gave two gasps and went.

Dr. Smith said that Neave’s food was not suitable for such a young, weakly child. An older and stronger one might have done on it. The change of food would be very detrimental, especially to Neave’s food. Dr Smith said, “Why cannot these nurses be supplied with an authorised list of the foods suitable for such children?” The coroner said, “You know they won’t comply with it. The mothers often buy just whatever food a shopkeeper recommends to them.”

Ads like the one for Neave’s Food came thick and fast during the war years, this was just one of many.

You can see the old editions of Old Moore’s Almanac in the National Library of Ireland in Dublin, free of charge. You can’t borrow the books, but you can take them into the reading rooms and have a look at wildly damaging ads from a bygone era.

If you are searching for old editions, you will need to know this information.

As always, the advice on the cover is: Beware of spurious editions.