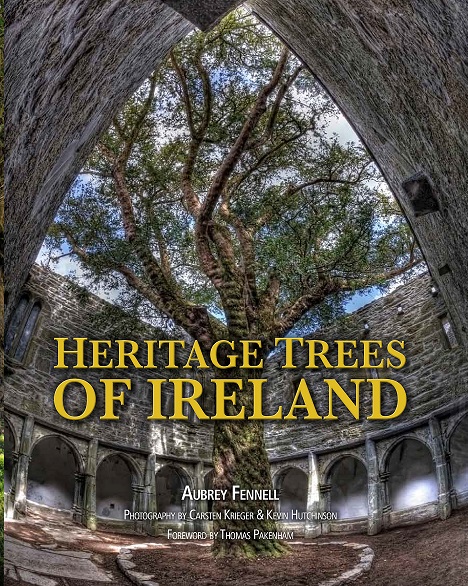

Enter a fascinating world of trees unique to Ireland with connections dating back over thousands of years.

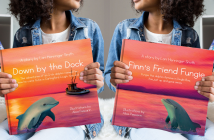

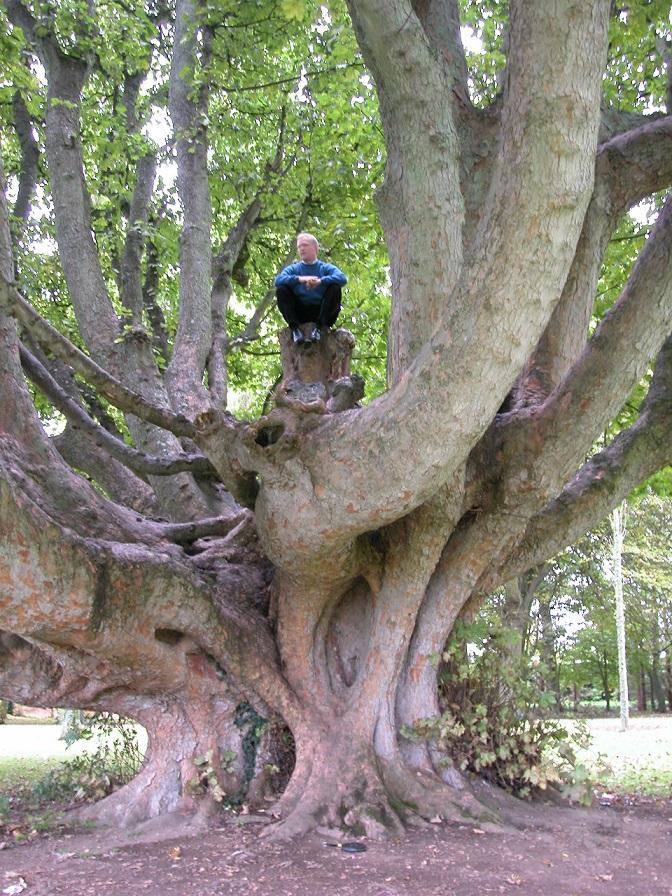

Author Aubrey Fennell with a tree friend.

Enter a fascinating world of trees unique to Ireland with connections dating back over thousands of years.

Trees are a precious part of Ireland’s heritage, some remarkable for age or size, location or aesthetic appeal, historical or folklore connections. Such trees are found in our native woodlands, historic parklands, along roadsides, in hedgerows, fields and in housing estates. Enamoured by trees, Aubrey Fennell, Carsten Krieger and Kevin Hutchinson have compiled a book about Ireland’s most fascinating trees. The book documents the stories behind 150 of these remarkable trees: rag trees, hanging trees, trees at holy wells, trees of exceptional size or age, trees associated with historic events, and trees important to the community. Well-known examples are the ‘Hungry’ Tree at King’s Inns, Dublin, that appears to be consuming a bench; Lady Gregory’s ‘Autograph’ Tree at Coole Park, Galway – a copper beech signed by W. B. Yeats, his brother Jack, George Bernard Shaw, John Masefield, Sean O’Casey and other famous people.

Here are some examples of some amazing arboreal friends.

THE KING OAK

Charleville Estate, Tullamore, County Offaly

Quercus robur︱Pedunculate Oak

HEIGHT: 19m

GIRTH: 8.29m

ACCESS: The tree is located on private property but can be viewed on the driveway from the entrance gate.

The King Oak, Charleville Estate, Tullamore, County Offaly

The mightiest oak on the edge of the mightiest oakwood in Ireland can be seen at Charleville Forest near Tullamore. This common oak forest is a remnant of what the Irish landscape must have looked like before the destruction and loss of our forests in medieval times. The status of common oak as an Irish native tree has often been debated by ecologists. Most of the oaks we see now were originally planted by landowners in the 18th and 19th centuries. But core-dating of the oaks at Charleville show them to be between 350 and 450 years old, a lot older than any known introduction.

Common or pedunculate oak woods are generally found on base-rich soils such as the limestone of the midlands. They often incorporate a mixture of ash, elm and downy birch above an understorey of hazel, hawthorn and spindle. There are many large barrel-chested oaks scattered through the adjoining parkland. Some are even bigger in girth than the King Oak but fall short of its majestic presence.

The King Oak grows near the Tullamore entrance to the Charleville estate. It is an amazing tree as four of its lower branches stretch out, dipping and rising and dipping again over the ground up to 27m away. It defies the laws of gravity. There is a tradition that should any of its branches snap off, a member of the Hutton-Bury family will die. They own the estate so they have taken the understandable precaution of supporting the branches with wooden props. They should have thought of a lightning conductor, because in 1963 a thunderbolt struck, creating a gash down the trunk to the ground. The head of the family died soon afterwards. Today the tree is a popular meeting point for young and old. This is a privately owned estate but visitors are welcome providing they treat the woods with respect. This is one Royal that any Irishman would have no problem bowing to.

GLENCORMAC YEW

Glencormac, Kilmacanogue, County Wicklow

Taxus baccata ︱ Yew

HEIGHT: 18m

GIRTH: 6.61m

ACCESS: The tree is located on privately owned property in the garden of Avoca Handweavers Shop/Restaurant and can be viewed by the public during advertised opening hours.

Glencormac Yew, Glencormac, Kilmacanogue, County Wicklow

The Glencormac yew has long been thought to be Ireland’s oldest and largest yew. Along with the Silken Thomas yew, for many years they were the only ones known to be over 6m in girth. Since the Tree Register was founded in 1999 another three such yews have been discovered. The earliest reference to yews in Ireland comes from Giraldus Cambrensis who visited here in the 13th century, and mentions that yews are commonly found in sacred places and old burial grounds. Scores of large ancient yews are still to be found in graveyards in Wales and England, but in Ireland they have not been given the same protection. Maybe during territorial disputes and warfare in ancient times, such sacred trees were destroyed as a particularly spiteful form of revenge.

The Glencormac yew can be seen at Avoca Handweavers in Kilmacanogue, beside the N11. Many huge eucalyptus and sequoias dot the grounds. At the bottom of the garden is a 300-year-old yew walk. At its end stands a much larger tree with a magnificent muscular trunk. It looks as if a hundred pythons have collectively decided to build a pyramid. It has been suggested that this tree’s proximity to a late 12th-century church indicates that the site was a resting place on the pilgrimage path to Glendalough, where a similar large yew once existed. No real evidence has surfaced for this conjecture.

It was 17ft/5.2m in girth in 1860, and is now about 22ft/6.7m, depending how far above ground it is measured. A dead stump a foot/30cm in diameter taken from the crown contained 170 annual rings. Debate among tree experts on the age of individual yew trees cannot be resolved as they hollow out after about 300 years. My own gut feeling is that this tree is no more than 600 years old. Visit the tree yourself, and its beautiful presence will make all arguments superfluous.

HAUNTED BUSH BY THE OLD BOG ROAD

Old Bog Road, Connemara, County Galway

Crataegus monogyna ︱ Hawthorn

HEIGHT: 2m

GIRTH: 0.38m

ACCESS: This tree is visible from the R341 known as the Old Bog Road, from Roundstone to Clifden.

Haunted Bush by the Old Bog Road, Old Bog Road, Connemara, County Galway

There is an 11km stretch between Cashel and Clifden in west Connemara called the ‘Old Bog Road’. The road winds its way through a desolate landscape of stone, bog and lake with nothing but the occasional sheep and the plaintive call of the curlew for company. This is no place to be caught out in the elements and back in the 19th century there was a hostelry called the Half-Way House which was a convenient stop for travellers and people walking home from fairs. Today, there is no habitation for miles around, and it is easy to pass the stone ruins of the former inn without noticing, as it merges into the rocky background. The other side of the road has a lone windswept hawthorn bush, no taller than a man, in splendid isolation, trimmed by hungry sheep. It is here where the story begins, although I cannot vouch for its authenticity, as it may have gained wings in intervening years.

Stand at the bush and look south as the land drops down to Lough Agaddy just over half a kilometre away. In the middle of the lake is an island covered in furze. This was home to a thief who preyed on travellers at the inn. He would first select a victim by making sure they were alone with no friends or family nearby. He would dispatch his victims close to the lone bush, and bury them in the bog on his retreat back to the island. He used a half barrel to float over and no one was able to follow. The Half-Way House closed a hundred years ago and the people who passed through have been forgotten and crumbled into dust – or have they? Look towards the lake: a scattering of holly and mountain ash are believed to be the reincarnation of those murdered souls, their blood rising annually in the red berries. Recently an old man has been seen sitting beside the hawthorn bush at the oddest of times. Could he be a traveller from another dimension?

ST MARY’S WELL, ROSSERK

Rosserk Abbey, Ballina, County Mayo

Crataegus monogyna ︱ Hawthorn

HEIGHT: 2m

GIRTH: 0.45m

ACCESS: This tree is located on private property which is open to public access.

St Mary’s Well, Rosserk, Rosserk Abbey, Ballina, County Mayo

A couple of kilometres north of Killala, by the mouth of the River Moy, signposts draw you to Rosserk Abbey which was founded by the Franciscans in about 1440. It is situated by the estuary, and is extolled as one of the most beautiful ruined abbeys in the country. It was created for a community of married people who were unable to be become nuns and monks but still wanted to adopt the monastic life. Just over half a kilometre before the abbey, another sign directs you to Tobermurray, or St Mary’s Well, and a five minute walk brings you to a grassy hollow with a stream dropping down to a sheltered sea inlet. That stream emerges from a spring at the bottom of a slope where an apparition of the Virgin Mary is said to have occurred in 1680. It is likely that St Mary’s Well was used for Mass during the penal times of the 18th century. A tiny stone vaulted chapel with a cross over the well has an inscription in Latin which reads, ‘this chapel was built in honour of the Blessed Virgin in the year of our Lord 1798 by John Lynott of Rosserk, Esq’. The well was venerated and people came to pray, seek cures and leave offerings. It was particularly noted for the cure of bad eyesight, and devotees washed their eyes and drank the water. Pattern day is on 15 August, when Mass is held.

What makes the shrine special is the presence of a small hawthorn growing out of the stone roof, with no appearance of roots, inside or out, connecting with the ground. Locals say that it first appeared about a hundred years ago, but there are no legends associated with its appearance, apart from the miracle of surviving in such an exposed and hungry place. It is 2m tall and 0.45m in girth, and had a fine crop of haws when I visited. It must be especially lovely garlanded in May blossom. There are other extraordinary trees growing in unusual places featured in the book, but this one beats them all.